Free E-Mail

Bible Studies

Beginning the Journey (for new Christians). en Español

Old Testament

Abraham

Jacob

Moses

Joshua

Gideon

David, Life of

Elijah

Psalms

Solomon

Songs of Ascent (Ps 120-135)

Isaiah

Advent/Messianic Scriptures

Daniel

Rebuild & Renew: Post-Exilic Books

Gospels

Christmas Incarnation

(Mt, Lk)

Sermon on the Mount

(Mt 5-7)

Mark

Luke's

Gospel

John's Gospel

7 Last Words of Christ

Parables

Jesus and the Kingdom

Resurrection

Apostle Peter

Acts

The Early Church

(Acts 1-12)

Apostle Paul

(Acts 12-28)

Paul's Epistles

Christ Powered Life (Rom 5-8)

1 Corinthians

2 Corinthians

Galatians

Ephesians

Vision for Church

(Eph)

Philippians

Colossians,

Philemon

1

& 2 Thessalonians

1 & 2 Timothy,

Titus

General Epistles

Hebrews

James

1 Peter

2 Peter, Jude

1, 2, and 3 John

Revelation

Revelation

Conquering Lamb of Revelation

Topical

Glorious Kingdom, The

Grace

Great Prayers

Holy Spirit, Disciple's Guide

Humility

Lamb of God

Listening for God's Voice

Lord's Supper

Names of God

Names of Jesus

Christian Art

About Us

Podcasts

Contact Us

Dr. Wilson's Books

Donations

Watercolors

Sitemap

46. The Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37)

by Dr. Ralph F. Wilson

Audio (28:39)

Gospel Parallels §143-144

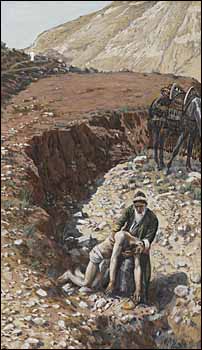

James J. Tissot, 'The Good Samaritan' (1886-94), gouache on gray wove paper, 10 x 5.3 in., Brooklyn Museum, New York. |

" 25 On one occasion an expert in the law stood up to test Jesus. 'Teacher,' he asked, 'what must I do to inherit eternal life?' 26 'What is written in the Law?' he replied. 'How do you read it?' 27 He answered: '"Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind"; and, "Love your neighbor as yourself."' 28 'You have answered correctly,' Jesus replied. 'Do this and you will live.' 29 But he wanted to justify himself, so he asked Jesus, 'And who is my neighbor?' 3

0 In reply Jesus said: 'A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, when he fell into the hands of robbers. They stripped him of his clothes, beat him and went away, leaving him half dead. 31 A priest happened to be going down the same road, and when he saw the man, he passed by on the other side. 32 So too, a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. 33 But a Samaritan, as he traveled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him. 34 He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, took him to an inn and took care of him. 35 The next day he took out two silver coins and gave them to the innkeeper. "Look after him," he said, "and when I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have."

36 'Which of these three do you think was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?' 37 The expert in the law replied, 'The one who had mercy on him.' Jesus told him, 'Go and do likewise.'" (Luke 10:25-37, NIV)

Of all Jesus' parables, none has worked its way deeper into the American consciousness as the Parable of the Good Samaritan. The phrase "Good Samaritan" is used to describe any person who goes out of his way to help another. It's a theme that newspaper reporters love to feature because it captures readers' attention and fires the imagination. The largest recreational vehicle club in the United States is termed the "Good Sam Club" from its ideal of members helping one another.

But the Parable of the Good Samaritan says more than, "It's good to help people in need." The parable is also about excuses. About self-justification. About letting oneself off the hook. Dig with me to mine the riches of the parable.

Sometime during the Judean part of Jesus' ministry -- we're not told exactly when and where394 -- Jesus encounters a lawyer, Greek nomikos, "legal expert, jurist, lawyer,"395 a man skilled in interpreting the Jewish Torah (i.e., the first five books of the Old Testament, also called the Pentateuch). It's fascinating to see that Luke places this incident directly following Jesus' rhapsody to his Father, "You have hidden these things from the wise and learned, and revealed them to children...." (10:21) The "children" are Jesus' disciples, his followers, who have just learned about spiritual power in the name of Jesus. Now we meet the "wise and learned," represented by a legal expert, schooled in all the intricacies and interpretations of the Torah, a very sophisticated scholar. The children and wise are placed in sharp contrast.

Do This and You Will Live (Luke 10:25-28)

"On one occasion an expert in the law stood up

to test Jesus. 'Teacher,' he asked, 'what must I do to inherit eternal life?'

'What is written in the Law?' he replied. 'How do you read it?'

He answered: '"Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul

and with all your strength and with all your mind"; and, "Love your neighbor as

yourself."'

'You have answered correctly,' Jesus replied. 'Do this and you will live.'"

(10:25-28)

The lawyer's question is an important one: "What must I do to inherit eternal life?" Later, the Rich Young Ruler asks Jesus the same question (18:18). In essence, he is asking Jesus to capsulize what is important for a Jew to do in order to be saved. And what is more important than salvation?

But Luke tells us that the lawyer has an underlying motive, "to test Jesus." The Greek word is ekpeirazō, "put to the test, try, tempt."396 In this case, the lawyer isn't trying to tempt Jesus in the sense of lead Jesus into sin. Rather, the skilled teacher of the law is testing this unofficial, Galilean lay teacher to see how well he will answer difficult theological questions. The lawyer's motive could be simple intellectual curiosity about Jesus' insight into the Scriptures. But he has doubtless already heard Jesus speak, or heard reports of Jesus' message. So his motive, more likely, is to see if he can expose Jesus' naiveté in contrast to his own sophistication. Perhaps intellectual pride or jealousy of Jesus' immense following prompt this testing. Jesus will face many such challenges in the Judean phase of his ministry: on rendering taxes to Caesar (Matthew 22:17-18: Mark 12:15; Luke 20:22-23), on divorce (Matthew 19:3; Mark 10:2), on the resurrection (Matthew 22:23-32), on doing some sign (Matthew 16:1; Mark 8:11; Luke 11:16), and on stoning a woman caught in the act of adultery (John 8:6).

In this case and in others, Jesus doesn't answer the question. Instead he appeals to the expert's self-perception of being an authority, and turns the question back to him. "'What is written in the Law?' Jesus replies 'How do you read it?'" (10:26) Jesus is saying, "You're an expert on the Torah. What does your reading tell you is the answer to your question?"

The legal expert's answer shows much insight. In fact, he agrees exactly with Jesus' own assessment of the Torah's essential message: "Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind"; and, "Love your neighbor as yourself," quoting Deuteronomy 6:5 and Leviticus 19:18, respectively.

Jesus compliments him on his answer: "You have answered correctly," and so in the balance of this relationship between expert and novice, Jesus now assumes the role of expert on the Law, commenting on the rightness or wrongness of another's interpretation. The lawyer who has sought to test Jesus is now himself being tested and evaluated.

But when you think about it, Jesus' compliment is remarkable. So often Jesus has to deal with Pharisees, whose understanding of the Law is all out of proportion. They emphasize the minor details and neglect the big picture; they "strain out gnats" but "swallow camels" (Matthew 23:23-24). But this man sees the big picture. He understands, or so it would seem, "justice, mercy, and faithfulness" that the Pharisees neglect (Matthew 23:23).

The lawyer recites what Jesus has termed the Great Commandment, to love God and love one's neighbor. "Do this and you will live," is Jesus' reply to the lawyer's question, "What must I do to inherit eternal life?"

Contrary to some who interpret this passage, I don't think that the issue is "works righteousness," a salvation based on doing good works. Rather the issue is: What is the quintessential message of the Torah? Let's not import Paul's important emphasis on faith vs. works into a Gospel context where it doesn't belong.

Who Is My Neighbor? (Luke 10:29)

"But he wanted to justify himself, so he asked Jesus, 'And who is my neighbor?'" (10:29)

The power of the truth that the lawyer has spoken is too much for him. By his own words he has correctly stated the heart of the Law: "Love your neighbor as yourself," and is feeling convicted by it. After all, he might say, the context of the verse he had quoted limits the definition of "neighbor": "Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against one of your people, but love your neighbor as yourself. I am the Lord." (Leviticus 19:18)

So, in typical lawyer fashion, he seeks to defend his position by closely defining words. What is your definition of "neighbor," he asks Jesus. At this point we see an exchange between a pair of rabbis, teachers. One has stated the essence of the law, and the other has acknowledged the truth of his answer. Now the first asks the second to clarify the answer. The rabbinical writings of the Talmud are full of carefully reasoned legal distinctions about when a law is in effect, and when it is not.

The Jews typically interpreted "neighbor," meaning "one who is near," in terms of members of the same people and religious community, that is, fellow Jews (as in Matthew 5:43-48). The Pharisees tended to exclude "ordinary people" from their definition. The Qumran community excluded "the sons of darkness" from their definition of neighbors.397

The lawyer agrees that the essence of the Torah is to love one's neighbor as oneself, but then seeks to limit the application of this to fellow Jews only. Love your own race and faith community, he believes, and you have fulfilled the law.

Luke tells us that his first motive is to "test" Jesus; his second motive is to "justify himself," to defend his own limited interpretation of the Torah. Here is a scholar struggling with integrity between his beliefs and actions.

Parables and Stories

"In reply Jesus said: 'A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho....'" (10:30)

If someone were to ask you the definition of "neighbor," you might respond with a carefully-worded definition, the kind of phrase you find in Webster's Dictionary. But Jesus answers with a parable. Parables are stories told to make a point. They aren't actual history, but they capture true-to-life details in such a way that hearers' identify with the elements of the story and can grasp the spiritual lesson of the story. There was no actual Good Samaritan that Jesus is referring to. But he is calling upon his hearers' awareness of the dangers of traveling alone on the Jericho-Jerusalem road, and from there, presenting a hypothetical situation designed to make a point.

Robbers on the Jericho Road (Luke 10:30)

"A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, when he fell into the hands of robbers. They stripped him of his clothes, beat him and went away, leaving him half dead." (10:30)

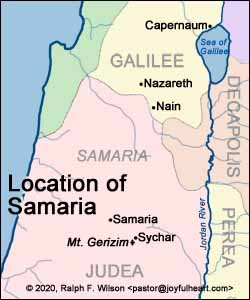

The Road from Jerusalem to Jericho (larger map) |

Jerusalem is located along the ridge of coastal mountains running north and south in Palestine. Jericho, on the other hand is located in the plain of the Jordan River, in a geological rift zone hundreds of feet below sea level. The 17 mile road that connects these two cities descends some 3,300 feet (1,000 meters) through desert and rocky country that could easily hide brigands or bandits. Josephus notes that Pompey destroyed a group of brigands here, and Jerome spoke of Arab robbers in his time.398 Law and order hasn't eliminated robbery. American legend thrives on stories of Jesse James robbing stage coaches. Modern-day city dwellers live in fear of mugging on streets and in subways.

The robbers on the Jericho Road were pretty desperate. Even if a man had little of value, they would attack him for the value of his clothing alone. But they didn't just threaten him and take his clothing. They stripped him of his clothing and then beat him, probably with wood staffs. The Greek uses two words to describe the beating: epitithēmi, "to lay on, inflict"399 and plēgē, "blow, stroke."400 They beat him in order to incapacitate him from following them, or perhaps to intimidate him from trying to identify them. Apparently, they didn't seek to kill him, however. Jesus says that they left him literally "half-dead" (Greek hēmithanēs). Jesus isn't telling of an actual man, of course, but adding some details in order to paint a picture. His listeners are now eager to see what happens to the unfortunate man.

Priests and Levites (Luke 10:31-32)

"A priest happened to be going down the same road, and when he saw the man, he passed by on the other side. So too, a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side." (10:31-32)

Jesus places in his story two well-known figures in society, priests and Levites. The priest would be returning to Jericho from service in the temple at Jerusalem -- Jericho was known as a principal residence for priests.401 In New Testament times, Levites were an order of cultic officials, inferior to the priests, but still a privileged group in society, responsible for the liturgy in the Temple and for policing the Temple.402 While both priests and Levites were from the tribe of Levi (descendants of Jacob's son Levi), the priests were also descendents of Aaron, the first High Priest.

In Jesus' story, both the priest and Levite see the wounded man and pass by on the other side of the road. They see the man's need but choose not to help.

"Typical!" the hearers are thinking. There were probably various anti-clerical stories circulating among the populace, and you can almost see Jesus' hearers nodding and smiling at the caricature. I'm sure that the legend of the hypocritical clergyman has been circulating since Biblical times.

The Excuse of Religious Purity

Some believe that the priest and Levite might have had some justification for their actions. After all, as temple officials they were especially concerned about ceremonial cleanness. The Law stated that the high priest "must not enter a place where there is a dead body. He must not make himself unclean, even for his father or mother" (Leviticus 21:11). Even a regular priest "will also be unclean if he touches something defiled by a corpse" (Leviticus 22:4; Ezekiel 24:25). What if the man lying beaten by the side of the road were dead? The man may not have been stirring. One can't be too careful, you know. According to scholar J. Mann, the Pharisees held that a priest would not be defiled by touching a dead body when there was nobody else available to perform the burial, but the Sadducees (that may have included many of the priests) contended that he would be defiled.403

On the other hand, the law is pretty clear about helping those who are in need, both man and beast, friend and foe -- even if he is your enemy!

"If you come across your enemy's ox or donkey wandering off, be sure to take it back to him. If you see the donkey of someone who hates you fallen down under its load, do not leave it there; be sure you help him with it." (Exodus 23:4-5)

"Do not gloat when your enemy falls;

when he stumbles, do not let your heart rejoice,

or the Lord will see and disapprove

and turn his wrath away from him." (Proverbs 24:17-18)

"If your enemy is hungry, give him food to eat;

if he is thirsty, give him water to drink.

In doing this, you will heap burning coals on his head,

and the Lord will reward you." (Proverbs 25:21-22)

And, of course, the very verse the lawyer had quoted makes the priest's and the Levite's obligations clear: "Love your neighbor as yourself. I am the Lord" (Leviticus 19:18).

Placing religious purity over helping a person who was perhaps still alive is gross hard-heartedness and selfishness. And walking on the other side of the road displays a deliberate "I don't want to know!" attitude. The less they saw about the man's condition, the less they would feel obligated to help him. After all, he might be dead and then there would be nothing they could be obligated to do. Our modern-day equivalent of this attitude is, "I don't want to get involved."

Samaritans, the Hated Step-Brothers

A priest, a Levite ... and the hearers would be expecting a Jewish layman to be the third and climatic character. Three people or situations are often found in stories of that period and our own (Matthew 25:14-30; Luke 19:11-27; 14:18-20; 20:10-12). But, no. Jesus introduces a Samaritan into the story.

Location of Samaria (larger map) |

The Samaritans were particularly hated in Jesus' day. They lived in an area south of Galilee and north of Judea, part of the old Northern Kingdom of Israel. In 721 BC Israel was conquered by Assyria, and Sargon II conducted a mass deportation of the entire region, carrying off some 27,270 captives and resettling the area with colonists from other parts of the Assyrian empire (2 Kings 17:24).404 Their descendents were looked upon as half-breeds and heretics by the Jews of Jerusalem. Though Samaritans believed in the Torah, they worshipped at Mt. Gerizim rather than Jerusalem (John 4:20-22). At times, relations between the Jews and Samaritans had been civil, but in Jesus' day feelings were definitely hostile. Sometime between 6 and 9 AD at midnight during a Passover, some Samaritans had deliberately scattered bones in the Jerusalem Temple in order to desecrate it.405 The Jews were outraged! What remained now was disdain and hatred, as John observed: "Jews do not associate with Samaritans" (John 4:9b).

For Jesus to introduce the Samaritan as the caring person, after a priest and a Levite had neglected mercy, must have been intended as an especially biting commentary on what passed for "mercy" among the pillars of Judaism.

Taking Pity upon the Man (Luke 10:33)

"But a Samaritan, as he traveled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him." (10:33)

The Samaritan traveler doesn't move over to the other side of the road, but when he sees the wounded man he takes pity on him. The word translated "pity" is Greek splanchizomai, "have pity, feel sympathy," from splanchnon, literally, "inward parts, entrails," figuratively of the seat of the emotions, in our usage, "heart."406 Love, sympathy, and mercy are motivated by the need of another, while withholding mercy is essentially an act of selfishness, of self-protection.

Binding Up His Wounds (Luke 10:34a)

"He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine." (10:34a)

The Samaritan binds up the wounds (Greek trauma) of the injured man, perhaps with his own head covering or by tearing strips from his garment. The Samaritan also pours on oil and wine as healing agents. Olive oil was widely employed to keep exposed parts of the skin supple, to relieve chafing, to soften wounds, and to heal bruises and lacerations.407 We can see something of the treatment of wounds in a passage from Isaiah that speaks in literal terms about spiritual sickness:

"From the sole of your foot to the top of your

head

there is no soundness --

only wounds and welts

and open sores,

not cleansed or bandaged

or soothed with oil." (Isaiah 1:6)

Wine, perhaps, was poured on for cleansing. Though they had no knowledge of germ theory, we know that wine, which ferments naturally to about 7% to 15% alcohol, would have had some disinfectant properties.408

Prepaying the Man's Hotel Bill (Luke 10:34b-35)

"Then he put the man on his own donkey, took him to an inn and took care of him. The next day he took out two silver coins and gave them to the innkeeper. 'Look after him,' he said, 'and when I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have.'" (10:34b-35)

The Samaritan's love of his neighbor proved costly. He used his own supplies to cleanse and soothe the man's wounds, his own clothing to bandage him, his own animal to carry him while the Samaritan himself walked, his own money to pay for his care, and his own reputation and credit to vouch for any further expenses the man's care would require. Love can be costly. But if we have the means to help, we are to extend ourselves. The Apostle John taught,

"If anyone has material possessions and sees his brother in need but has no pity on him, how can the love of God be in him? Dear children, let us not love with words or tongue but with actions and in truth." (1 John 3:17-18)

There wasn't an emergency room where the Samaritan could take the man. Instead, he took him to a hotel or "motel" and cared for the man himself that night. Edersheim sees the inn as a khan or hostelry, found by the side of roads, providing free lodging to the traveler. They also provided food for both man and beast, for which they would charge.409

It seems likely that the Samaritan was a merchant who frequently traveled this way and had stayed at this inn before. He trusts the innkeeper enough to advance him money to care for the wounded man. And he promises the innkeeper -- who also seems to trust the Samaritan -- to reimburse him for any additional costs when he returns from his trip. The Samaritan's mercy is a generous mercy. A mercy that doesn't just keep the letter of the law, but its spirit as well. "Whatever he needs," is the limit of his mercy.

Who Was Neighbor to the Man? (Luke 10:36-37a)

"'Which of these three do you think was a

neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?'

The expert in the law replied, 'The one who had mercy on him.'" (10:36-37a)

Now Jesus punches home his point. He asks the lawyer which of the three proved to be a neighbor to the wounded man, and the lawyer is forced to reply, "The one who had mercy on him."

The Greek word used is eleos. In classical Greek, eleos is the emotion roused by contact with an affliction which comes undeservedly on someone else. The New Testament meaning of eleos draws on the Hebrew concept of hesed, faithfulness between individuals that results in human kindness, mercy, and pity.410 One summary of godly piety is found in Micah 6:8:

"He has showed you, O man, what is good.

And what does the Lord require of you?

To act justly and to love mercy (Hebrew

hesed, Greek Septuagint eleos),

and to walk humbly with your God."

Mercy is required of us (Isaiah 58:6-7; Hosea 6:6). Jesus commands his disciples very specifically: "Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful" (Luke 6:36).

The lawyer began by asking for a definition of "neighbor" in order to justify limiting his love to his fellow Jews only. Jesus doesn't define "neighbor" in so many words, but his story makes it clear that our neighbor is whoever has a need. It doesn't matter who they are. Jesus' command to love our neighbor as ourselves knows no self-satisfying limits.

Go and Do Likewise (Luke 10:37b)

"Jesus told him, 'Go and do likewise.'" (10:37b)

Jesus isn't content just to define what "neighbor" means. He commands us to do as the Samaritan does, to show mercy to our fellow man who is in need.

Are Christians to be "do-gooders"? Yes, I suppose. But our motivation for doing good must be love for others, an interest in meeting their basic needs, a heart of mercy that is moved by compassion.

I must ask myself, what we -- as disciples of Jesus -- are supposed to learn from this story. And for me the answer is to examine my own heart. What motivates me? How much have selfishness and a dogged adherence to my own agenda leached away the mercy that Jesus holds dear and wants to flourish in my heart through his Holy Spirit? I may be efficient, but am I merciful? When "push comes to shove" do I put myself first, or do I put the needs of others first? I think of the words to the song,

"Only one life, 'twill soon be past.

Only what's done for Christ will last."411

For me, Jesus' command, "Go and do likewise," means that I must value acts of mercy over personal productivity. What does it mean for you?

Prayer

Father, the parable of the Good Samaritan reminds me that sometimes I seek to justify my own selfishness. I'm a lot like the lawyer. I've studied much and know a great deal about theology and the Bible. But knowledge isn't what you seek. It is my heart that you seek, and the acts of love and mercy that should flow freely out of my heart. Forgive me, Lord, for my selfishness. Forgive me for excusing myself. And let your flame of love and mercy flare up afresh in my heart and consume my selfish tendencies. I pray this as a disciple -- in Jesus' name. Amen.

Key Verse

"But a Samaritan, as he traveled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him." (Luke 10:33)

Questions

Click on the link below to discuss on the forum one or more of the questions

that follow -- your choice.

https://www.joyfulheart.com/forums/topic/1962-46-good-samaritan/

- If you were to select three themes that this passage discusses, what would they be? What is the chief theme?

- How is it possible to be able to correctly recite the greatest commandments in the Bible (10:27-28), and still not have them "installed" in your life?

- Have you ever heard a Christian try to justify a less-than-Christian attitude or action? Why do we constantly try to justify our actions? What motivates justifying ourselves?

- How did the lawyer justify his actions? How do you think the priest and Levite in this story justified their actions?

- Extra Credit: Jesus wasn't reciting an historical incident; he was creating a hypothetical incident for teaching purposes. Why do you think that the hero of the story was a Samaritan? What was Jesus' point by including the Samaritan? How do you think the lawyer felt about it?

- What does the parable of the Good Samaritan illustrate? What does it teach us about love? About mercy? About selfishness?

- How are we to emulate the Good Samaritan by "doing likewise"? What is God speaking to you from this passage?

Lessons compiled in 805-page book in paperback, Kindle, & PDF. |

Endnotes

[394] The Greek word used, idou, sometimes translated "Behold," is to be translated variously according to the passage's context. Here it probably means something like "There was ...." See Shorter Lexicon, p. 92.

[395] Nomikos, Shorter Lexicon, p. 133.

[396] Ekpeirazō, Shorter Lexicon, p. 60.

[397] Marshall, Luke, p. 444. He cites 1QS 1:10; 9:21 for the Qumran sect's interpretation, and Strack and Billerback I, 353-364 for common Jewish interpretations.

[398] Marshall, Luke, p. 447, cites Josephus, Wars of the Jews 4:474, Strabo 16:2:41; and Jerome, in Jerem. 3:2. Joachim Jeremias, Jerusalem, p. 52, discusses additional incidents, including whole villages around Jerusalem known to be nests of thieves.

[399] Epitithēmi, Shorter Lexicon, p. 76.

[400] Plēgē, Shorter Lexicon, p. 160.

[401] Marshall, Luke, p. 448, cites Strack and Billerback II, 66, 180.

[402] Marshall, Luke, p. 448.

[403] Marshall, Luke, p. 448, cites J. Mann, "Jesus and the Sadducean Priests, Luke 10:25-37," Jewish Quarterly Review, ns 6, 1915, 415-422.

[404] D.J. Wiseman, "Samaria," NBD, p. 1061-1062.

[405] Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 18.2.2.

[406] Splanchizomai, Shorter Lexicon, p. 184.

[407] Roland K. Harrison, "Heal," ISBE 2:640-647.

[408] Edersheim, Life and Times 2:238 cites Jer. Ber. 3a and Shabb. 134a as indicating oil and wine as the common dressing for wounds. N. Angelotti and P. Martini, "Treatment of skin ulcers and wounds through the centuries," (Minerva Med. 1997 Jan-Feb 88(1-2):49-55) note that Hippocrates washed ulcers with wine and after having softened them by oil, he dressed them with fig leaves. Marshall, Luke, p. 449, affirms that the use of wine and oil as healing agents is well-attested, citing Shab. 14:2; 19;4; Strack and Billerback I, 428; and Theophrastus, Hist. Plant 9:11:1.

[409] Edersheim, Life and Times 2:239.

[410] Rudolf Bultmann, oleos, ktl., TDNT 2:477-487.

[411] C.T. Studd (1860-1931), "Only One Life."

Copyright © 2025, Ralph F. Wilson. <pastor![]() joyfulheart.com> All rights reserved. A single copy of this article is free. Do not put this on a website. See legal, copyright, and reprint information.

joyfulheart.com> All rights reserved. A single copy of this article is free. Do not put this on a website. See legal, copyright, and reprint information.

|

|

In-depth Bible study books

You can purchase one of Dr. Wilson's complete Bible studies in PDF, Kindle, or paperback format -- currently 48 books in the JesusWalk Bible Study Series.

Old Testament

- Abraham, Faith of

- Jacob, Life of

- Moses the Reluctant Leader

- Joshua

- Gideon

- David, Life of

- Elijah

- Psalms

- Solomon

- Songs of Ascent (Psalms 120-134)

- Isaiah

- 28 Advent Scriptures (Messianic)

- Daniel

- Rebuild & Renew: Post-Exilic Books

Gospels

- Christmas Incarnation (Mt, Lk)

- Sermon on the Mount (Mt 5-7)

- Luke's Gospel

- John's Gospel

- Seven Last Words of Christ

- Parables

- Jesus and the Kingdom of God

- Resurrection and Easter Faith

- Apostle Peter

Acts

Pauline Epistles

- Romans 5-8 (Christ-Powered Life)

- 1 Corinthians

- 2 Corinthians

- Galatians

- Ephesians

- Philippians

- Colossians, Philemon

- 1 & 2 Thessalonians

- 1 &2 Timothy, Titus

General Epistles

Revelation

Topical

To be notified about future articles, stories, and Bible studies, why don't you subscribe to our free newsletter, The Joyful Heart, by placing your e-mail address in the box below. We respect your

To be notified about future articles, stories, and Bible studies, why don't you subscribe to our free newsletter, The Joyful Heart, by placing your e-mail address in the box below. We respect your