Free E-Mail

Bible Studies

Beginning the Journey (for new Christians). en Español

Old Testament

Abraham

Jacob

Moses

Joshua

Gideon

David, Life of

Elijah

Psalms

Solomon

Songs of Ascent (Ps 120-135)

Isaiah

Advent/Messianic Scriptures

Daniel

Rebuild & Renew: Post-Exilic Books

Gospels

Christmas Incarnation

(Mt, Lk)

Sermon on the Mount

(Mt 5-7)

Mark

Luke's

Gospel

John's Gospel

7 Last Words of Christ

Parables

Jesus and the Kingdom

Resurrection

Apostle Peter

Acts

The Early Church

(Acts 1-12)

Apostle Paul

(Acts 12-28)

Paul's Epistles

Christ Powered Life (Rom 5-8)

1 Corinthians

2 Corinthians

Galatians

Ephesians

Vision for Church

(Eph)

Philippians

Colossians,

Philemon

1

& 2 Thessalonians

1 & 2 Timothy,

Titus

General Epistles

Hebrews

James

1 Peter

2 Peter, Jude

1, 2, and 3 John

Revelation

Revelation

Conquering Lamb of Revelation

Topical

Glorious Kingdom, The

Grace

Great Prayers

Holy Spirit, Disciple's Guide

Humility

Lamb of God

Listening for God's Voice

Lord's Supper

Names of God

Names of Jesus

Christian Art

About Us

Podcasts

Contact Us

Dr. Wilson's Books

Donations

Watercolors

Sitemap

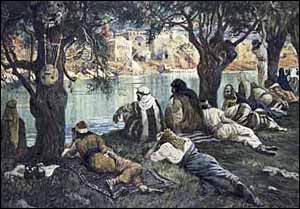

James J. Tissot, 'By the Waters of Babylon' (1896-1903), The Jewish Museum, New York. Notice the instruments hanging from the trees. Tissot illustrates Psalm 137:1-2: " By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept when we remembered Zion. There on the poplars we hung our harps...." |

Any study of the dating of the Book of Daniel must begin with the dates imbedded within the text. Nearly every chapter is tied to some historical event, beginning in 605 BC when Daniel and his friends were deported from Jerusalem to Babylon to serve in the court of Nebuchadnezzar the Great. In addition to the "court stories" in chapters 1-6, Daniel's visions are dated as follows:

- Nebuchadnezzar's Dream, "in the second year of his reign," about 603 BC (2:1).

- Daniel's Dream of Four Beasts, "in the first year of Belshazzar king of Babylon," about 553 BC (7:1).

- Daniel's Vision of a Ram and a Goat, "in the third year of King Belshazzar's reign," about 550 BC (8:1).

- Daniel's Prayer of Intercession and Vision of the Seventy Weeks, "in the first year of Darius son of Xerxes," about 539 BC, (9:1).

- Daniel's Vision of the Kings of the North and South, "in the third year of Cyrus king of Persia," about 536 BC (10:1).

Based on the internal dating, Daniel has been dated in the mid-sixth century BC by both Jews and Christians from the earliest times. The only exception to this was a pagan Neoplatonic philosopher named Porphyry of Tyre (c. 234-305 AD), who, in a 15-volume work Against the Christians, tried to discredit Jewish and Christian prophecy by claiming that Daniel's visions were written by "someone who lived in Judea at the time of Antiochus Epiphanes; and so instead of predicting the future, this writer describes what has already happened."[305] This was refuted by Jerome in his Commentary on Daniel (407 AD) and there it lay for more than a thousand years.

During the Enlightenment, when liberal scholars began to question the dating and authorship of dozens of Old and New Testament books, that began to change. Since the early 1800s, Porphyry's position became the basis of the German literary-critical movement's dating, spreading the theory far and wide, so that by the mid-twentieth century this was the dominant scholarly position. They didn't believe that accurate prophecy of the future was possible. Their view was that the Hebrew prophets were "forthtellers" not "foretellers" -- though a careful study of the prophets shows that this is a clear overstatement. However, it is only fair to say that some respected evangelical scholars, such as Goldingay,[306] F.F. Bruce,[307] and N.T. Wright,[308] also hold to a late dating.

The late-dating of Daniel is primarily based on claims that:

- Daniel contains historical inaccuracies concerning sixth century kings and events.

- Daniel contains Greek words that wouldn't have been possible if it had been written in the sixth century.

- Daniel's predictions of the future are "too accurate" to be authentic prophecy. Therefore, they must have been written after the fact.

- Apocalyptic literature didn't flourish until after 200 BC.

Questions of History Accuracy

Those who hold a late date for the Book of Daniel question the historical accuracy of several passages in Daniel that purport to be from the sixth century. We'll look at them one by one.

1. The siege of Jerusalem in the third year of Jehoiakim (1:1)

The very first verse in Daniel reads:

"In the third year of the reign of Jehoiakim king of Judah, Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon came to Jerusalem and besieged it." (1:1)

This is disputed on two grounds: (1) that Nebuchadnezzar's assault on Jerusalem took place in the fourth year of Jehoiakim's reign (Jeremiah 46:2), not in the third year (Daniel 1:1); and (2) that Nebuchadnezzar didn't actually besiege Jerusalem.

The reason for the discrepancy between the third and fourth year is a difference in reckoning systems, pure and simple. Palestinian and Egyptian reckoning (most common in the Old Testament) counts the months between a king's accession and the new year as a complete year. The Babylonians, however, began to count a king's reign from the first new year after accession. Since the Book of Daniel is written from the point of view of a court officer in Babylon, using the Babylonian system makes good sense. In fact, it is an argument for the early dating of Daniel.

Late-daters dispute that Nebuchadnezzar actually besieged Jerusalem. The Hebrew verb is ṣûr. The root means "to make secure a valuable object, such as money." Applied to military action it means "to relentlessly attack an opponent's stronghold."[309] Though 2 Kings doesn't specifically use the term "besiege," we read that Nebuchadnezzar "came up," forcing Jehoiakim to be his vassal (2 Kings 24:1; 2 Chronicles 36:6). Whether the Babylonian army entered into a full siege Jerusalem in 605 BC, or just the presence of troops in the area caused enough of a threat, the bottom line is that Jerusalem capitulated, and at one point Jehoiakim was forced to be a vassal of Babylon.

2. King Belshazzar

Some later-daters complain that while Belshazzar is called "king" in Daniel 5:1, he wasn't the king. Technically, Belshazzar's father Nabonidus (556-539 BC) was king and Belshazzar served as co-regent with his father about 553-539 BC. Nevertheless, Belshazzar functioned as king in Babylon, since Nabonidus was engaged in war and other pursuits far from the capital for nearly a full decade. To see a late date for Daniel based on this point is weak.

3. Darius the Mede (5:30; 6:28)

Darius the Mede who appears as the king of Babylon under the Persians (5:30; 6:28) is unknown to history outside of Daniel. Two alternative explanations of the identity of Darius the Mede have been suggested. (1) D.J. Wiseman argues that Darius the Mede was merely an alternative title for Cyrus the Persian. In this case, 6:28 would be translated (legitimately): "So this Daniel prospered during the reign of Darius, namely the reign of Cyrus the Persian."[310] I don't find this compelling.

Whitcomb argues that Darius the Mede was in fact Gubaru, the governor of Babylon and the region Beyond the River (Abar-nahara), exercising virtually royal powers in Babylon and hence not improperly called "king."[311] I think this is more likely. We still don't know anything about this Darius the Mede from contemporary documents.

4. Use of the Term 'Chaldean'

Some have questioned the use of the word "Chaldean" in Daniel. The Aramaic word is kaśdîm. It can be translated as either "Chaldean" by race, or as "learned," of the class of Magi (a technical term derived from the reputation of the Chaldean wise men), depending upon the context.[312] In Daniel's day, Babylon was ruled by leaders drawn from the clan of the Chaldeans who lived in the area around Babylon. To claim that Daniel is late based on its use of this word is weak.

Questions of Language

The late date of Daniel was supported by scholars who claimed that the Aramaic sections in Daniel belonged to a later period. However, more recent studies have found that the Aramaic used in Daniel was used in the courts and chancelleries from the seventh century BC on, and tends to support an early date for Daniel.[313]

The presence of Persian and Greek loanwords in the text of Daniel, primarily in the words for musical instruments, was long taken as a proof that Daniel was written in the Greek period after Alexander's conquests. It is now generally recognized that there were many earlier contacts with the Greeks and Persians, including Greek colonies in Egypt in the mid-seventh century BC and Greek mercenary troops in the Battle of Carchemish in 605 BC. Also, the names of musical instruments could well be found along with the instruments at the Persian court.[314] Today, linguistic arguments for a late date of Daniel are considered quite weak.

The Rise of Apocalyptic Literature

One argument for a late date comes from the observation that apocalyptic literature seems to have been popular between 200 BC and 100 AD. However, most apocalyptic literature seems to copy the style of Daniel, as one of the earliest examples of apocalyptic. If the copies occur between 200 BC and 100 AD, the prototype doesn't have to be from the same period.

Daniel seems to have been widely accepted as authoritative Scripture from the second century BC onwards.[315] Daniel was a popular book in the Qumran community, with eight fragments of the Hebrew text found at Qumran. The oldest of these (4QDanc; 4Q114) seems to have been copied in the late second century BC, only a half century after the Maccabean period.[316] If Daniel had been written in the Maccabean period, fifty years just isn't enough time for it to have been considered canonical, authoritative Scripture.

Pseudonymous Writings

Those who contend for a late date of Daniel argue that it is an example of the pseudonymous quasi-prophecy that is a common feature of Jewish apocalyptic literature of the period.[317] They claim that everyone of the time knew that the attributed authors weren't the real authors. Longman disagrees, and I share his concerns.

"For this type of literature to work -- that is, if it is to achieve its intended effect on an audience -- they cannot know that it is quasi-prophecy. In order to build up the reader's confidence that God controls history and that he is sovereign over the future, the reader must believe that the prophecy is precisely that."[318]

When a book gives in the text specific dates for its composition, to say that it was written hundreds of years later implies an intent to deceive the readers that the prophecy was actually written by the prophet Daniel. To make Daniel a deception doesn't do justice to its widespread use as authentic Scripture by Jesus, the apostles, and the early church. I don't think you can get around that.

Available in book formats: paperback, Kindle, PDF |

In conclusion, despite arguments to the contrary, I believe that an excellent case can be made for a sixth century dating of the Book of Daniel. My conclusion is that the Book of Daniel seems to have been written in Babylon by Daniel near the end of his life, about 530 BC -- or compiled in Babylon by his disciples from Daniel's writings shortly thereafter.

Endnotes

[305] Summarized by Jerome, Commentary on Daniel, 35, translated by Gleason Archer (1958).

[306] Goldingay, Daniel, pp. 321-329.

[307] F. F. Bruce, Biblical Exegesis in the Qumran Texts (London: Tyndale Press, 1960), pp. 67-74.

[308] N.T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God (Fortress, 2003), pp. 108-128.

[309] Ṣûr, TWOT #1898.

[310] D.J.A. Clines, "Darius," ISBE 1:867.

[311] D.J.A. Clines, "Darius," ISBE 1:867. This Gubaru is not to be confused with Ugbaru [Gobryas], the governor of Gutium who captured Babylon for Cyrus but died three weeks later.

[312] Kaśdîm, BDB 109, 2.

[313] Harrison, Introduction, pp. 1123-1125.

[314] See Harrison, Introduction, pp. 126-127; TWOT #2887.

[315] There is an apparent borrowing of Daniel 7:9-10 in the pseudepigraphic 1 Enoch 14:18-22, which was written prior to 150 BC.

[316] Eugene Ulrich, "Daniel Manuscripts from Qumran. Part 1: A Preliminary Edition of 4 QDan a,"Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 268 (November, 1987), pp. 17-37.

[317] E.C. Lucas ("Daniel: Book of," DOTP, p. 120) writes, "Pseudonymous quasi-prophecy is a common feature of Jewish apocalypses. We should not reject it as an unworthy literary form simply because we do not understand the psychology of both author and readers involved in its use."

[318] Longman, Daniel, p. 272. E.C. Lucas ("Daniel: Book of," DOTP, p. 121) asserts, "Attributing the visions to Daniel was not an attempt to deceive people; it was an expression of the group's sense of solidarity and continuity with their past traditions." In my opinion, Lucas's rationalization is unsupportable.

Copyright © 2025, Ralph F. Wilson. <pastor![]() joyfulheart.com> All rights reserved. A single copy of this article is free. Do not put this on a website. See legal, copyright, and reprint information.

joyfulheart.com> All rights reserved. A single copy of this article is free. Do not put this on a website. See legal, copyright, and reprint information.

|

|

In-depth Bible study books

You can purchase one of Dr. Wilson's complete Bible studies in PDF, Kindle, or paperback format -- currently 48 books in the JesusWalk Bible Study Series.

Old Testament

- Abraham, Faith of

- Jacob, Life of

- Moses the Reluctant Leader

- Joshua

- Gideon

- David, Life of

- Elijah

- Psalms

- Solomon

- Songs of Ascent (Psalms 120-134)

- Isaiah

- 28 Advent Scriptures (Messianic)

- Daniel

- Rebuild & Renew: Post-Exilic Books

Gospels

- Christmas Incarnation (Mt, Lk)

- Sermon on the Mount (Mt 5-7)

- Luke's Gospel

- John's Gospel

- Seven Last Words of Christ

- Parables

- Jesus and the Kingdom of God

- Resurrection and Easter Faith

- Apostle Peter

Acts

Pauline Epistles

- Romans 5-8 (Christ-Powered Life)

- 1 Corinthians

- 2 Corinthians

- Galatians

- Ephesians

- Philippians

- Colossians, Philemon

- 1 & 2 Thessalonians

- 1 &2 Timothy, Titus

General Epistles

Revelation

Topical